VIII.5.36 Pompeii. Terme repubblicane.

Republican Baths.

Excavated 1882, 1950 and 2015.

(Strada dei Teatri 6).

According to SAP, this is the oldest of the public baths in Pompeii.

Aside from initial superficial excavations under Sogliano in 1882, the first systematic investigations of the Republican Baths were carried out under Amedeo Maiuri in 1950 who documented the layout.

See Maiuri A., Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 1950,

pp. 116-136

Following this research, the building remained largely forgotten for several decades and the standing remains were visible, but largely obscured by covering vegetation.

New excavations began in 2015 by Freie Universität Berlin - Institut für Klassische Archäologie in collaboration with University of Oxford and Parco Archeologico di Pompeii.

According to Fagan, this small establishment occupies the south-east corner of insula VIII.5, with an entrance at 36. It was advantageously situated near the entrance to the triangular forum and the theatre. It was a double building with a palaestra like the other two baths, but on a much smaller scale, occupying only a section of the insula in which it stood. In 1999 it was overgrown and inaccessible.

Maiuri postulated a construction date of c. 90-80 B.C. This was based on the building materials and the primitive form of the hypocaust – whereby the floor was raised not on pillars but on continuous walls broken by diagonal openings. Maiuri thought it had been a privately-owned facility as, unlike the Stabian and Forum Baths, no public inscriptions have been found, if any ever existed. It seems to have been abandoned in Augustan times, after half a century of operation, perhaps put out of business by the improvements in the comfort and amenities of the Stabian Baths in the Augustan extension. Seneca condemns a fickle public that abandoned older baths as more luxurious ones became available.

According to the Parco

Archeologico di Pompeii website, the [recent]

excavations in the Republican Baths have allowed them to obtain new important

results for the knowledge of the urban development of Pompeii, since the whole

area has been used since the Archaic period. The thermal complex was built

during the II century BC, on an area previously occupied by industrial plants.

The building has two stages of modification, which demonstrate the effort made

by builders to adapt the building to new technological standards. Despite this,

the building was abandoned by the end of the 1st century BC to be merged with

the neighbouring Casa della Calce, of which it came to constitute a second

garden. In the last phase, just before the eruption of 79 AD, the whole area

seems to have been converted into a sort of building materials deposit, where

building materials were extracted and selected.

See Terme Repubblicane on SAP web site

See Fagan G. G., 1999. Bathing in Public in the Roman World. Ann Arbor: Univ Michigan, p. 59-60 and note 64.

See Seneca Ep. 86.8-9. Moral letters to Lucilius (Epistulae morales ad Lucilium) - Letter 86 - on Wikisource

See Maiuri A., Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 1950,

p. 116-136.

2015-2016 excavations

The project is a research collaboration

between the Freie Universität Berlin and the University of Oxford.

Archaeological levels can be traced back to

the Mercato Eruption (Pomici di Mercato) of Vesuvius around 7000 BC.

The earliest traces of human activity, in the shape of isolated sherds, date

back to the Bronze age. More regular use of the area can be traced to the Iron

Age, for which occupation evidence in the form of isolated postholes and a

hearth could be identified. Before the mid-2nd century BC, the site was used

for some form of industrial activity as indicated by several water features and

dumps of fuel ash. The baths themselves were not constructed until the middle

or latter half of the 2nd century BC and underwent several modifications until

their abandonment and demolition in the late 1st century BC. The area then

became part of the Casa della Calce and was used as a garden surrounded by

porticoes and rooms. In the last period of use, probably post-dating the

earthquake of AD 62, several large quarry pits were dug across the site, some

of which were refilled with building waste once they were no longer used.

All excavated areas had been affected by

trenches dug by Maiuri, resulting in incomplete or disturbed stratigraphic

sequences. Nonetheless, it was possible to identify and reconstruct a

substantial overall Matrix of contexts reaching from the Bronze Age through to

79AD. While most data remains preliminary at present and requires further

analysis, some interesting observations can already be made: the laconicum

(identified as room 30) appears to have been constructed by the 2nd century BC,

probably during its the earliest years. It underwent a major phase of

reconstruction from an initially rectangular space to its current rounded

interior shape. This is likely also to have occurred during the 2nd century BC.

A further phase of rebuilding and modification dates to the 1st century BC. The

development of the various identified phases of the praefurnium (identified as

room 17) remains far more problematic: created originally as a rectangular

space with six heating ducts for the two sets of caldaria and immersion pools,

it was repeatedly modified, reduced in extent and reconstructed in order to

modify heat flow and firing accessibility, as well as in response to the

changing needs of the modified baths complex as a whole in its various phases.

2019 season

In March and April 2019, a field season of

the project “Bathing Culture and the Development of Urban Space: Case Study

Pompeii”, was carried out in the Republican Baths (VIII 5, 36) at Pompeii.

The season was focused on studying the

finds and cleaning some areas to clarify specific questions.

The ceramics team completed the study of

the material from the Republican Baths.

Cleaning served to clarify two major

questions: first, characteristics and function of certain water management

features, which Thomas Heide investigates for his dissertation at the Freie

Universität Berlin. Cleaning included: a double drainage hole in the

southwestern corner of the men’s tepidarium; a large, deep settling basin in

the southeastern corner of the men’s apodyterium; and the part of the baths’

drainage channel that is located in taberna 35 of the Casa della Calce (VIII,

5, 28).

Second, the design and development of the

southwestern corner of the baths, which Maiuri had excavated but barely

mentioned in his report from 1950, were investigated. The chronology of the southwestern

room of the baths (room 34, numbering system of project) could be clarified, correlating

well with the development of the entire lot, as established in previous

seasons: 1) service corridor with entrance from the street for the baths (c.

150-30/20 BC); 2) room decorated with Second Style wall paintings, accessible

only from the new garden peristyle of the Casa della Calce (30/20 BC); 3)

installation of a latrine along the south wall of the room, when the garden

peristyle was remodelled and provided with more rooms (sometime between 30/20

BC and AD 62); 4) room used as a dump site for debris after AD 62. In the room

to the north of this room (room 26, numbering system of project) a limekiln,

which Maiuri had excavated but not identified and described, was rediscovered.

This limekiln was installed for one of the remodelling phases in the early

Imperial period, but destroyed already before the

eruption of Vesuvius and filled with debris.

Author: Monika Trümper

See Freie

Universität Berlin - Institut für Klassische Archäologie

See FastiOnline folder fastionline.org Pompeii Republican Baths VIII.5.36

See Bathing Culture and the Development of Urban Space: Case Study Pompeii Freie Universität Berlin - Institut für Klassische Archäologie

VIII.6, Pompeii, on left. September 2015.

Vicolo delle Pareti Rosse looking west. VIII.5.36 side wall, on right.

VIII.6, Pompeii, on left. December 2004. Vicolo delle Pareti Rosse looking west. VIII.5.36 side wall, on right.

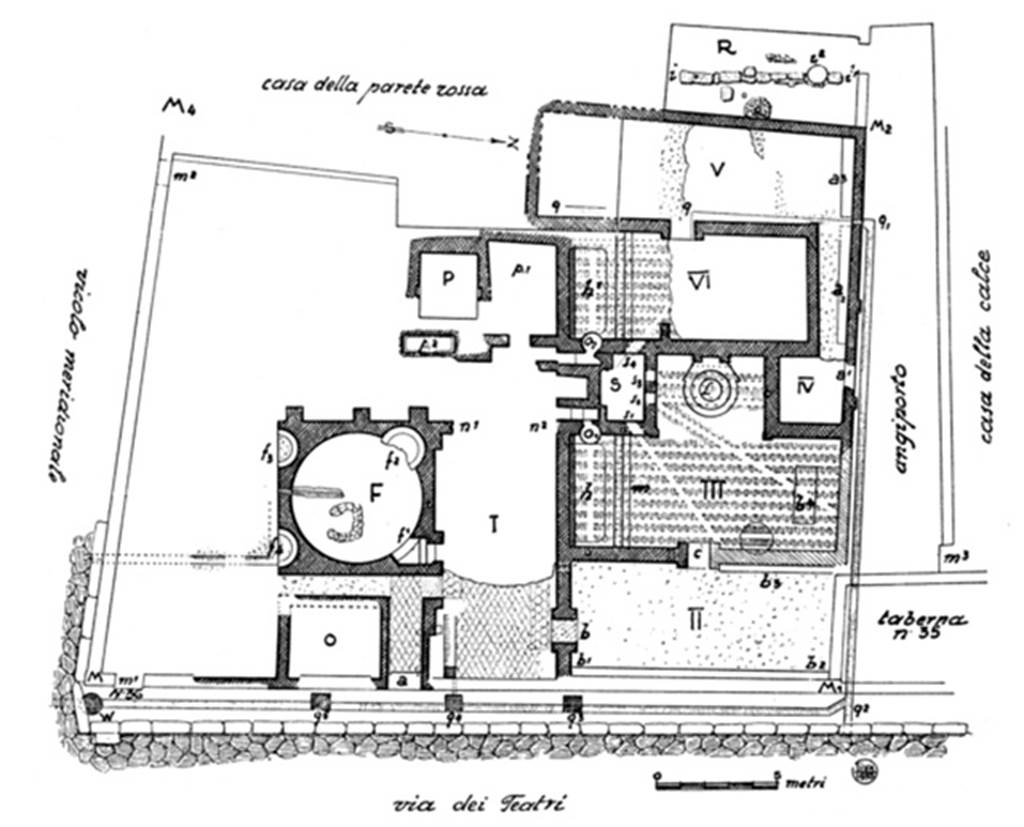

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. 1950 Maiuri plan of Terme repubblicane or Republican Baths.

Maiuri describes this as “free of later construction”.

See Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 1950,

p. 117, fig. 1.

According to

Maiuri –

Entrance (a) – the main entrance on Via dei Teatri,

from which one entered into the first large room (I), from which one had

access to a side of the Frigidarium (F), from the other side by means of

a vestibule, into a rectangular room (II) with function of a Waiting

room or a Tepidarium, and from this to the Caldarium (III).

The Baths had a second entrance (a’) – an entrance, still recognisable, from the north side on the angiportus, (later abolished), from which, by entering a square room (IV), and through a corridor, one reached a room that is also rectangular (V), (mutilated by the construction of the adjacent house), from which there was also access to a caldarium (VI) recognisable by the special preparation of the suspensurae.

The praefurnium is recognised in room S in addition to the two circular furnaces (o1 and o2), which were used, as we shall see, to heat the water of the two basins (h and h’); finally in P there is a Well for the water supply of the baths, in p1 a service room, perhaps a woodshed for feeding the furnaces, in p2 a residue of a basin/tank.

The few remains that lie beneath the later buildings along the southern side do not allow us to recognize their specific purpose.

The space for a real palaestra is missing: but it cannot be excluded that there was a portico or free space (xystus) in connection with the frigidarium.

The presence of two entrances and the repetition of the two caldaria preceded by other rooms with a common praefurnium, allows us to know that the layout of the baths was divided in two sectors – male and female: the men’s baths open onto a public roadway: secluded in the corner, which could also be closed by a gate, was the entrance to the women’s baths.

See Maiuri, A. Notizie

degli Scavi, 1949-50, (p,119).

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. Description by Maiuri.

See Maiuri, A. Notizie

degli Scavi di Antichità, 1949-50, (p,119).

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. Description by Maiuri.

See Maiuri, A. Notizie

degli Scavi di Antichità, 1949-50, (p,119).

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. Description by Maiuri.

See Maiuri, A. Notizie

degli Scavi di Antichità, 1949-50, (p,119-120).

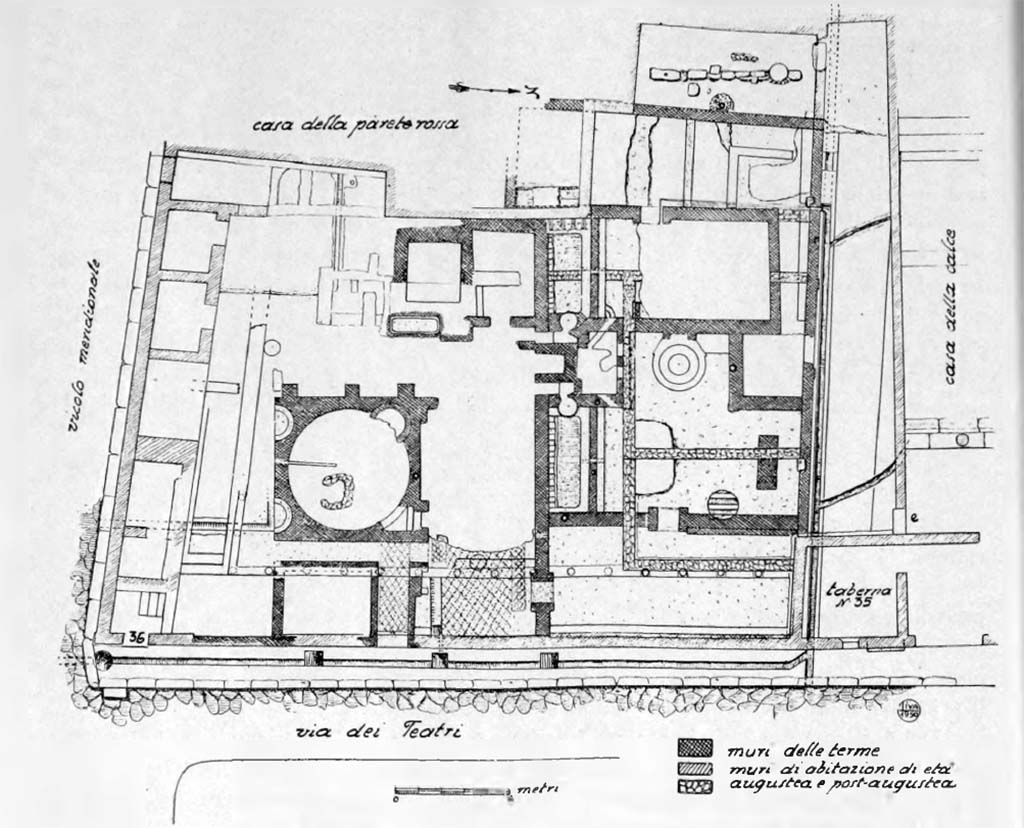

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. 1950 Maiuri plan of phase II of Terme repubblicane or Republican Baths.

According to Maiuri, with the closure of the baths, the area came into the hands of the owner of the adjacent "Casa della Calce" and was transformed into a dwelling area, by demolishing at least 2/3 of the high wall of the thermal baths and the raising of a little less or a little more than a metre on the floor of the rooms of the original building. After the first transformation follows a second that mutates and alters completely the character and the plan of the first dwelling, intersecting and overlapping the walls of the baths, it is not easy to untangle and determine the limits, the nature and the character of the two houses. You could still recognize three periods: a first transformation occurred in the Augustan age shortly after the baths were closed; a second in the Claudian era before the year of the earthquake; a third in the last years of the city with a few adaptations related to the use of the area as a garden.

See Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 1950,

p. 133-4, fig. 11.

See Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 1947,

p. 157.

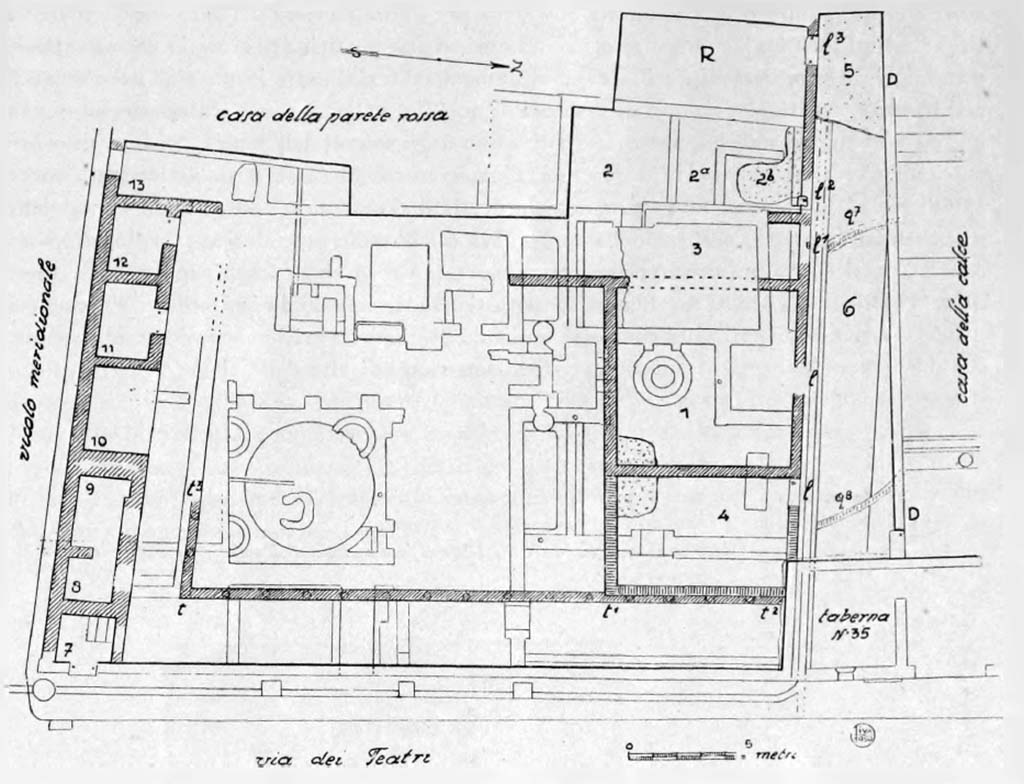

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. 1950 Maiuri plan of phase III of Terme repubblicane or Republican Baths.

According to Maiuri, after this first transformation, which for the entire Augustan age and perhaps also Tiberian, gave the closed baths a distinctly noble character not unbecoming to the rest of the nearby home, there was a subsequent transformation inspired by a more practical use of space: inspired by family reasons, more than anything else. At the large oecus or triclinium hall (n. 1) another minor oecus of the eastern side was added (4) overlapping one of the walls on the last five intercolumns of the garden portico (t1-t2), also equipped with an access threshold towards the peristyle of the "Casa della Calce". The date of this second transformation can be fixed to the Claudian or Neronian age on the basis above all to the many elements of the 4th style wall decoration found in the remains.

See Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 1950,

p. 135, fig. 12.

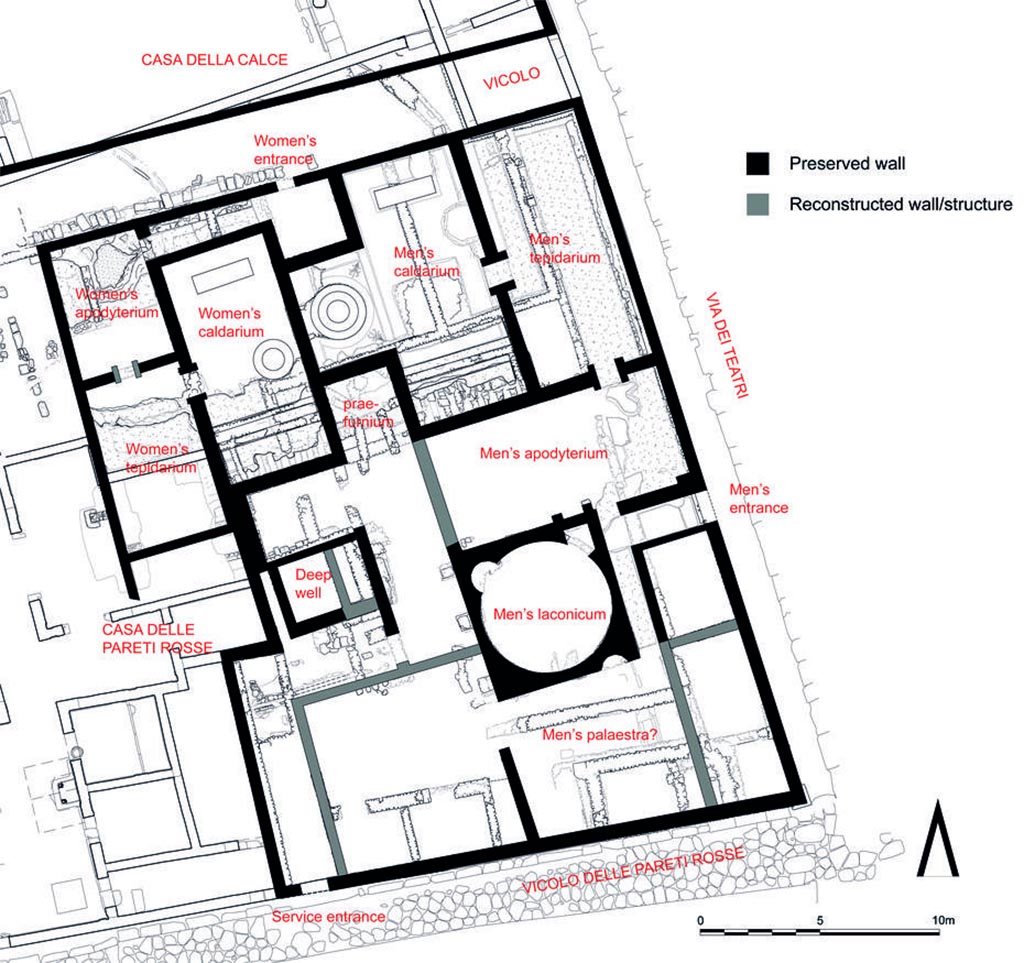

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. 1950 Plan of Terme repubblicane or Republican Baths.

Preliminary

reconstruction of the original baths (on top of the new state plan), built

around 150 BC

Photo courtesy of Freie Universität Berlin.

See Bathing Culture and the Development of Urban Space: FU Berlin

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October 2023.

Looking west along Vicolo delle Pareti Rosse on south side

of present-day entrance doorway. Photo

courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October

2023. Entrance doorway. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. September 2015. Entrance doorway in south-west corner, looking west.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. September 2015. Looking north along west side of Via dei Teatri.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. September 2015. Looking south-west along wall on west side of Via dei Teatri.

VIII.5.36, Pompeii. June 1962.

Looking west towards entrance doorway, from outside the Triangular Forum. Photo courtesy of Rick Bauer.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. December 2004. Entrance doorway.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October 2023. Looking west from entrance doorway. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October 2022. Looking west from entrance doorway. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October 2022. Looking west along rooms on south side, from entrance doorway. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. December 2006. Looking west from entrance.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October 2022. Looking north-west across rooms on south side. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. December 2006. Looking south towards room in south-west corner.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. December 2006. Looking towards south-west corner, detail.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October

2023.

Looking north-west

from entrance doorway, with site of the Well (P), on left, and Praefurnium (S),

in centre.

On the right is the

Frigidarium with the remains of one of the niches (f2) in the north-west

corner. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October

2023.

Looking north-west

from entrance doorway with detail from praefurnium. Photo courtesy of Klaus

Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. September 2015. Praefurnium.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October 2022. Looking north-west from entrance. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October 2022. Looking north-west. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. December 2006. Looking north-west from entrance.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. December 2006. Looking towards west side, with site of Well (P) near wall, in the centre.

According to Maiuri -

Well and water system.

“The water in service of the baths was supplied by a Well (P) which, like all the wells prior to the channelling of water in Pompeii, drew on the water-table at a depth of about twenty metres……….”

“Finally, connected to the well are the basins (p1-p2) which are very deteriorated and which, due to their smallness, seem to belong more to the earliest phase than to the last phase of the baths”.

See Maiuri, A. Notizie

degli Scavi, 1949-50, (p.128).

(Pozzo e

impianto idrico

L’acqua in

servizio della terma veniva fornite da un pozzo (P)

che, a somiglianza di tutti i pozzi precedenti la canalizzazione dell’acqua a

Pompei, attingeva la falda freatica a circa venti metri di profondità……….

Connesse con

il pozzo sono infine le vasche (p1 – p2) molto deteriorate e che, per la loro

piccolezza, sembrano appartenere più alla fase anteriore che alla fase ultima

della terma.)

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. December 2006. Looking north-west from entrance.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. December 2006. Looking north-west from entrance.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. December 2006. Looking north-west from entrance.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October 2023. Looking north from Vicolo delle Pareti Rosse.

The doorway into Room II from the vestibule, can be seen on the upper right side. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October 2023.

Looking north from Vicolo delle Pareti Rosse, detail of suspensurae under flooring. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October 2022.

Looking north from Vicolo delle Pareti Rosse, with the site of the Frigidarium, in centre. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October 2022.

Looking north towards Frigidarium, from room on south side near Vicolo delle Pareti Rosse. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

According to Maiuri –

“The Frigidarium (F) is exclusively part of the men’s bath, and has the typical structural form of the Pompeian frigidaria of the Stabian Baths and Forum Baths. It has a square plan on the outside, a circular plan on the inside with a single door (f1) in the north-east corner in place of one of the niches.

Emptied and stripped of all coverings, it no longer retains any trace of the circular basin and the steps that led to it. The structure, although it appears rougher and with more collected material, is coeval with the rest of the bath: here too you can see the re-used Sarno stone blocks used in the corners and at the head of the jambs. The only trace that remains of the water system are the remains of a cemented and mortar-framed terracotta pipe, at the bottom.

Instead of four niches on the inside, there are two on the inside and two on the outside; and of the two internal ones, one is used as an entrance doorway (f1), the other (f2) inserted at the rear and in place of another entrance that was later closed: the two external niches (f3-f4) facing an area that could, as mentioned, have been used as a Xystus, if not a Gymnasium, seem rather to be scholae used for resting on.”

See Maiuri, A. Notizie

degli Scavi, 1949-50, (p.120).

(Il

frigidarium (F) fa parte esclusivamente del bagno maschile, e presenta le

tipiche forme struttive dei frigidaria pompeiani delle Terme Stabiane e delle

Terme del Foro. A pianta quadrata esternamente, a pianta circolare internamente

con un’unica porticina (f1) ricavata nell’angolo nord-est al posto d’una delle

nicchie. Svuotato e spogliato d’ogni rivestimento, non conserva più alcuna

traccia della vasca circolare e dei gradini che vi adducevano. La struttura,

per quanto appaia più rozza e con materiale più raccogliticcio, è coeva col

resto della terma: si osservano anche qui i blocchi

di rimpiego in pietra di Sarno usati negli spigoli e alle testate degli

stipiti. La sola traccia che resta dell’impianto idrico soni i resti al fondo

d’una tubazione di terracotta cementati e incorniciati di malta.

In luogo di

quattro nicche all’interno, se ne hanno due

all’interno e due all’esterno; e delle due interne una e usata quale porta

d’ingresso (f1), l’altra (f2) inserita posteriormente e al posto di un altro

ingresso che venne successivamente richiuso: le due nicchie esterne (f3-f4)

rivolte verso un’area che poteva, come s’è accennato, aver ufficio di xystus,

se non proprio di palestra, sembrano piuttosto scholae di riposo.)

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October

2023. Looking north-east from Vicolo delle Pareti Rosse. Photo courtesy of

Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. October 2022. Looking east from Vicolo delle Pareti Rosse. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009. Taken from VIII.5.28. Looking south towards (present-day) entrance in corner, centre left.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009.

Taken from VIII.5.28. Looking south across angiportus at east end, towards site of men’s caldarium.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009.

Looking south-east towards Triangular Forum. Taken from VIII.5.28 across site of room III, men’s caldarium.

Room II with function of a waiting room or a tepidarium would have been on the left.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009. Taken from VIII.5.28. Looking south across site of room III, men’s caldarium.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009.

Detail of underground feature, ?suspensurae. Taken from

VIII.5.28. Looking south.

According to NdS –

“The room has unfortunately undergone the greatest alterations both from the crossing of the rear walls and the elevation of the floor (see fig. 11), and also from a large circular hole drilled in the floor, but the original surviving walls and floor allow us to recognise its primitive shape.”

See Maiuri, A. Notizie

degli Scavi, 1949-50, (p.121-22).

(L’ambiente ha

purtroppo subito le maggiori alterazioni sia dall’attraversamento dei muri

posteriori e dalla sopraelevazione del pavimento (cfr. fig. 11), sia anche da

un grosso foro circolare praticato nel pavimento ma i muri e il pavimento

originari superstiti permettono di riconoscerne la primitiva forma.)

Suspensurae.

“As Mau observed in the first partial and unfinished investigations of 1882, the suspensurae present us with a completely new type and, because of their greater undoubted antiquity, they constitute the oldest evidence that we have of this kind of thermal system.

The suspensurae, that is (see fig.7) instead of being formed by pillars of bricks or isodomic blocks, are made up of masonry walls, which run longitudinally from north to south in the direction of the major axis of the two boilers: they support a tile slab and above this the ruderation of the floor; they rest at the bottom on top of a simple layer of earth.”

See Maiuri, A. Notizie

degli Scavi, 1949-50, (p.129).

(Come ebbe ad

osservare il Mau nei primi parziali e incompiuti saggi del 1882, le suspensurae

ci presentano di un tipo affatto nuovo e, per la loro maggiore indubbia

vetusta, vengono a costituire la più antica testimonianza che si abbia di tal

genere di impianto termico.)

Le suspensurae

cioè, (fig.7) invece di essere formate da pilastrini di laterizi o di

blocchetti isodomici, sono costituite da muretti in fabbrica, che corrono

longitudinalmente da nord a sud nel senso cioè

dell’asse maggiore dei due caldaria: reggono un solarino di tegole e al di sopra di questo la ruderatio del pavimento; poggiano in basso sopra un

semplice strato di battuto.)

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009. Taken from VIII.5.28. Looking south.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009. Taken from VIII.5.28. Looking south across site of men’s caldarium on left, with labrum, on right.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009. Taken from VIII.5.28. Looking south-west.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. September 2015. Men’s labrum.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. 1950, men’s labrum and caldarium at time

of excavation. Looking west.

See Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 1950,

p. 118, fig. 3.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009. Taken from VIII.5.28.

Looking south-west across angiportus towards room IV, in centre with tree stems.

A doorway from the angiportus would have led through room IV into the women’s section of the baths, on right.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009.

Taken from VIII.5.28. Looking across angiportus towards Room IV with doorway (blocked) into the women’s baths.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009.

Taken from VIII.5.28. Looking towards west side and Room VI, women’s caldarium, in centre with Room V, at its rear.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009. Taken from VIII.5.28. Looking west along angiportus.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009. Taken from VIII.5.28. Remains of painted plaster in north-west corner.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009. Painted plaster in north-west corner. Taken from VIII.5.28.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009. Taken from VIII.5.28. Remains of painted plaster in centre of west wall.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. March 2009. Taken from VIII.5.28. Looking south-west across labrum in men’s caldarium.

VIII.5.36 Pompeii. September 2015. Looking south-west towards west side, over wall in Via del Teatri.